As you step off the plane at Kakuma Airstrip, you’ll immediately be greeted by a scene of dry heat, dusty murram, shrubs, and surrounding hills, with a seasonal river nearby. Despite the harsh environment, the residents of Kakuma and Kalobeyei exude warmth and approachability, embracing a positive attitude towards life and practicing gratitude.

Background of Kakuma and Kalobeyei Refugee Camps

Kakuma and Kalobeyei camps occupy a dry, desolate land with few trees. Kakuma Refugee Camp was initially established in 1992 to accommodate Sudanese refugees; today it accommodates refugees and asylum seekers from all over sub-Saharan Africa, including Somalia, Ethiopia, Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Uganda. Just 29.2km north of Kakuma, the settlement of Kalobeyei was created in 2015 as an extension of Kakuma.

Stuctural and spatial differences

While Kakuma is characterized by dusty, unpaved roads and crowded, makeshift paper and cardboard houses, Kalobeyei is made up of permanent structures set apart from one another along paved roads. As we visited schools within both Kakuma and Kalobeyei during our two weeks of data collection, these structural and spatial differences were striking. Kakuma is a larger and more established camp, covering a significant area of land. It consists of several zones and sectors, with a relatively more developed infrastructure. The camp has schools, healthcare facilities, markets, churches, mosques, and various community services. While, Kalobeyei camp was designed with a more innovative approach, focusing on a town-like setting rather than a traditional camp. It incorporates a “planned village” concept with a town center and smaller village clusters. The camp features semi-permanent housing units, markets, communal spaces, and shared facilities.

Efforts for self-reliance and development

Kakuma Refugee Camp was erected in response to the arrival of the Sudanese “Lost Boys”, who were children fleeing the violence in Sudan in 1992. By 2023, the average refugee at Kakuma spends 17 years living in the camp. Following the new influx of South Sudanese refugees after renewed conflict broke out in South Sudan in 2013. Kalobeyei was to represent a settlement approach, as opposed to the refugee camp approach as taken in Kakuma, in order to enable refugees to become more self-reliant in the long term via the establishment of Kalobeyei Integrated Social and Economic Development Program (KISEDP). This program aims to promote self-reliance by providing refugees with opportunities for education, vocational training, and skills development. Through the implementation of a self-help group model, the approach encourages refugees to form small groups based on common interests or skills and engage in income-generating activities. The adoption of a land-sharing framework between host communities and refugees. Unlike traditional refugee camps where refugees are confined to specific areas, Kalobeyei allows refugees to settle on plots of land alongside the host community.

This is aimed at reducing aid dependency and providing sustainable pathways to a future in Kenya.

Experiences during data collection

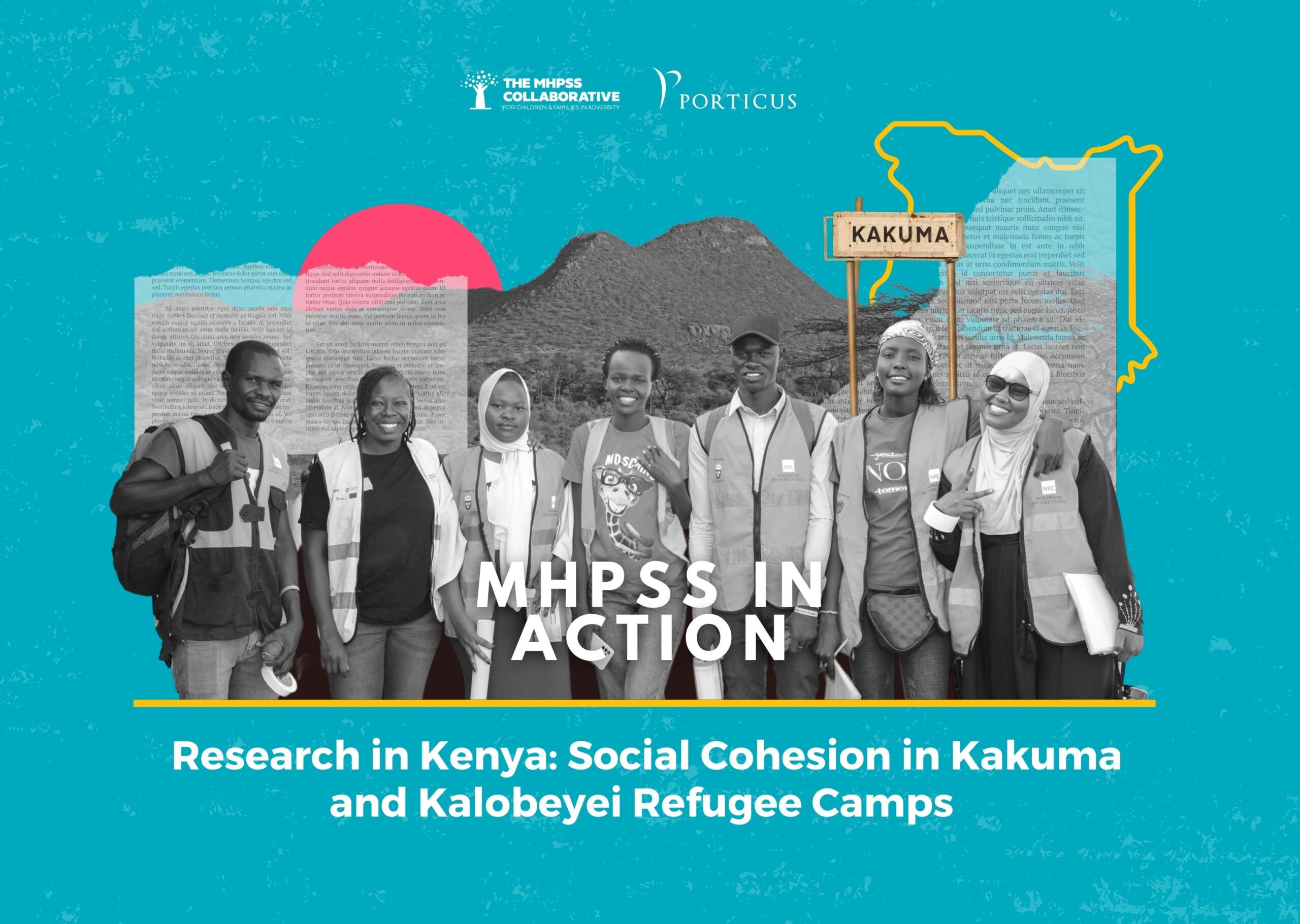

Our data collection team was led by Tess Pamela Olwala with on the ground support from Jennifer Flemming, and with the contributions of fieldwork from six enumerators living in Kakuma. As a group, we traveled to nine schools in just over two weeks of data collection. We were greeted with enthusiasm by the children, teachers, and school staff. The hospitality and eagerness to contribute valuable insights made us feel genuinely welcome in each location. Additionally, we had the opportunity to interact with the local community, including a memorable visit to a café in Kakuma at the end of the first week. This encounter allowed us to engage with the residents on a personal level, fostering understanding and collaboration.

Throughout data collection, we faced challenges but also real highlights and positive experiences. Our enumerator team had done little qualitative data collection prior, but with training and initial support became competent, skilled focus group facilitators with training and support. This transformation was a testament to their dedication and adaptability. At the end of it all, one of them became employed based on the experience that they had on this project with a recommendation letter from the Lead Researcher, Jennifer Flemming.

With the beauty of linguistic diversity comes some communication challenges. During the data collection in Kakuma and Kalobeyei, various languages were spoken by different groups. Our team had to be adaptive to the ways in which we were able to collect data to assure that we could represent as many perspectives as possible. For example, we relied on the linguistic skills of our diverse enumerator team, such as two of them running a caregiver focus group discussion due to their language proficiency. This diversity proved to be a considerable advantage.

Challenges faced by refugees

We saw and heard of many real-life experiences and challenges of different people who live or work in Kakuma and Kalobeyei. These included: lack of access to reliable affordable energy, language barriers, access to medical services, housing problems, lack of clean water for domestic use and poor sanitation, cultural differences, prejudice and racism, and overcrowding which makes residents vulnerable to diseases.

We heard about the lack of communication with families in the home country and/ or countries of asylum, ongoing mental health issues due to trauma, including survivor guilt and financial difficulties. We heard about how business owners and employers take advantage of the cheap labor supply of refugees living in the camps. We were told how the presence of international organizations helping with the crisis boosts demand for products and services such as food, housing and transport and the effect of inflated prices for goods.

Children observed in schools have experienced trauma and stress disorders due to their experiences and daily stressors in the camp. This was exhibited by social withdrawal, depression, and other behaviors. During data collection, we saw this firsthand through things like anxiety, PTSD, adjustment disorders and some of them being withdrawn. In these cases, it was common for the data collector to feel emotionally overwhelmed. We tried to discuss and unpack these feelings in the evenings as a team, and to provide opportunities for the enumerators to share as well.

In conclusion, our research in Kenya’s Kakuma and Kalobeyei Refugee Camps highlights the remarkable resilience and warmth of the residents, despite the challenging conditions they face. Kalobeyei’s innovative approach towards self-reliance shows promise, while Kakuma’s established infrastructure provides essential services. However, both camps grapple with various challenges, from language barriers to mental health issues and limited resources. Addressing these difficulties requires continued support and collaborative efforts from the international community to foster social cohesion and improve the lives of the refugees in these camps.

Note: Six enumerators supported data collection with learners, teachers, and caregivers in all locations. These enumerators were Jesca Alepar, Joseph Esinyen, Fatuma Mohamed, Regina Ekidor, Godffrey Lowoto, and Mwanakombo Omar.

This blog highlights reflections from our field team in Kenya, as part of a larger, three-country research project. To learn more about the research itself, as well as the other locations, SEE HERE.